Principles over Technique

The Krav Maga self-defense system is based on principles. We do have specific techniques, of course, but students should never mistake the technique for the absolute truth. When looking at the techniques, keep this in mind: The technique is the beginning of your understanding of self-defense, not the end. For example, here you see a defense against a bearhug. The defender creates leverage on the attacker’s neck by reaching around with her far-side hand, catching his face and his nose, and peeling or rolling his chin off her chest.

This is an excellent technique…but it is only an example of the principle. You can perform a similar technique by using the near-side hand and digging/pushing against the attacker’s nose and eyes. Is one technique better than the other? No! In one situation the first may be better, in a second situation the second may give better results.

The point is that you must not mistake the technique for the principle. The technique (as shown) is to reach around with your arm…but the principle is to create leverage on the neck.

As instructors, we know that we must start with actual technique. If we give students abstract principles, they will have nowhere to begin their training. This would be like plucking the strings on a guitar, describing music theory, and then handing the instrument to a new student and asking him to figure out a song for himself. He would feel lost. Instead, we teach him the notes, we help him build simple songs and chords, and soon he understands that the variations of those notes and chords are nearly limitless. So it is with defensive tactics: We start with basic structure so that information can be delivered effectively. By the end of his training, the student will be able to grasp the theory and make his own music.

Fewer Techniques That Solve More Problems

Our approach has always been to find one general movement that deals with as many variations in the attack as possible. It is absolutely impossible to create one unique defense against every possible type of attack. Life just doesn’t work that way. If we teach you 300 defenses against 300 attacks, you’ll go outside, and be assaulted by attack No. 301.

Instead, we try to create one movement that addresses as many variations as possible (using principles as discussed in What is Krav Maga?). This yields a simpler, more refined system that is easier to recall under stress. The simpler the system, the more decisive your actions will be because you will not be confused by options.

There is a well-known theory in the study of human movement and reaction known as Hick’s Law or the Hick-Hyman Law. Essential, this law states that the more choices a human being has to a particular stimulus, the longer his overall response time will be. Extended response times are a bad thing in self-defense situations. Therefore, we want to reduce overall response time. There are two ways to do this: a) train more and b) simplify the system.

There is a well-known theory in the study of human movement and reaction known as Hick’s Law or the Hick-Hyman Law. Essential, this law states that the more choices a human being has to a particular stimulus, the longer his overall response time will be. Extended response times are a bad thing in self-defense situations. Therefore, we want to reduce overall response time. There are two ways to do this: a) train more and b) simplify the system.

There is certainly nothing wrong with training more. The more you train, the better you will be. However, Krav Maga is designed for those who cannot train more, and even if you do have time to train, you will still benefit from a refined, efficient system.

Our system is built to reduce your options so that you do not hesitate under stress. When presented with a life-threatening situation, you should react decisively and aggressively, determined to neutralize the threat so that you and your loved ones are safe.

Even if you train enough to overcome the hesitation-due-to-options issue, there is another reason to simplify your choices: stress. Simply put, stress reduces performance. Increased training can reduce the impact of stress, but rarely does that impact fall to zero.

Here is a simple example of the impact of stress has on your performance. Imagine that we laid a long piece of wood, a 2×4, on the ground in front of you, then asked you to walk across it without touching the ground. Could you do it? Of course you could!

Next, we lay the same wooden plank across the gap between two tall buildings. Could you walk across it then? Why not? The wooden plank is strong enough to support you. Gravity is always constant, so you are not being pulled down any harder. Why can’t you do it?

The answer is simple: stress. The consequence of falling are now much greater. Your heart rate goes up, adrenaline floods your body, you begin to perspire, your muscles tighten. These and other physical and mental responses combine to impair your performance.

Again, training time reduces the impact of stress, but rarely brings it to zero. And since you will only need self-defense techniques when you are under stress, an effective self-defense system seeks to simplify the physical movements and the decision making so that you can perform as well as possible.

Examples of Stress Training

Many books and videos deliver a significant amount of information about the techniques and principles of Krav Maga but, by its nature, they cannot simulate Krav Maga training. Real training involves creative stress drills and applying the techniques and principles under various types of pressure. For our perspective, no technique or response is really learned until it’s tested in dynamic situations.

We strongly recommend that you perform stress drills under the supervision of a trained instructor. Krav Maga instructors certified by Krav Maga Worldwide and the Krav Maga Association of America go through an intense training program that includes lectures and discussions on physiology and sports kinesiology. In addition, they attend lectures specifically on safety in training and creating training drills so that the drills they offer are both productive and safe. Ultimately, all the training you do is at your own risk; however, participating in training drills under the supervision of a certified instructor will give you the highest measures of both safety and intensity.

Some training drills can be both simple and effective. Once you’ve learned defenses from two different types of chokes, simply close your eyes, stand passively, and wait for your partner to attack you with either of those chokes. Once you feel the attack, open your eyes, realize which attack is coming, and react immediately and appropriately. This is the simplest version of a stress drill, and it’s quite effective.

More intense versions of these drills include distractions and disturbances. Here is an example involving one defender, three people with large pads, and one attacker. The pad holders begin to hit and push the defender, who can cover himself but cannot attack the pads. He allows himself to be jostled around so that his balance and vision are impaired. At any time, the attacker can grab the defender with any attack (limited to those attacks the defender has learned to deal with). The defender must react immediately. The pad holders then immediately go back to disturbing the defender.

More intense versions of these drills include distractions and disturbances. Here is an example involving one defender, three people with large pads, and one attacker. The pad holders begin to hit and push the defender, who can cover himself but cannot attack the pads. He allows himself to be jostled around so that his balance and vision are impaired. At any time, the attacker can grab the defender with any attack (limited to those attacks the defender has learned to deal with). The defender must react immediately. The pad holders then immediately go back to disturbing the defender.

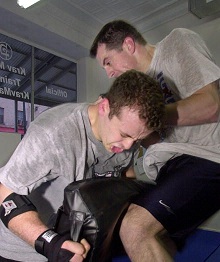

Here’s a variation of the drill above, featuring one defender, two people with large pads, and one attacker. Note that this version allows the defender to work on at least one specific strike, and is designed to exhaust the defender and add groundfighting as well:

The defender begins to strike one pad with punches, elbows, knees, etc. The other pad holder smacks the defender with his pad, at which point the defender pivots with a hammerfist and continues with strikes. This continues. At any point, the attacker closes in, catches the defender from behind, takes him down, and gets on top in a full mount. The defender allows the attacker to take him down – a more intense version of the exercise involves the defender attempting to prevent the takedown, but this requires greater skill on the parts of both attacker and defender to avoid injury.) This drill is exhausting!

We have hundreds of such drills that allow our students to learn how to apply the techniques they’ve learned. It is the only way to truly prepare for a violent encounter on the street.